BOOK NOTES, PHILOSOPHY, POLITICS

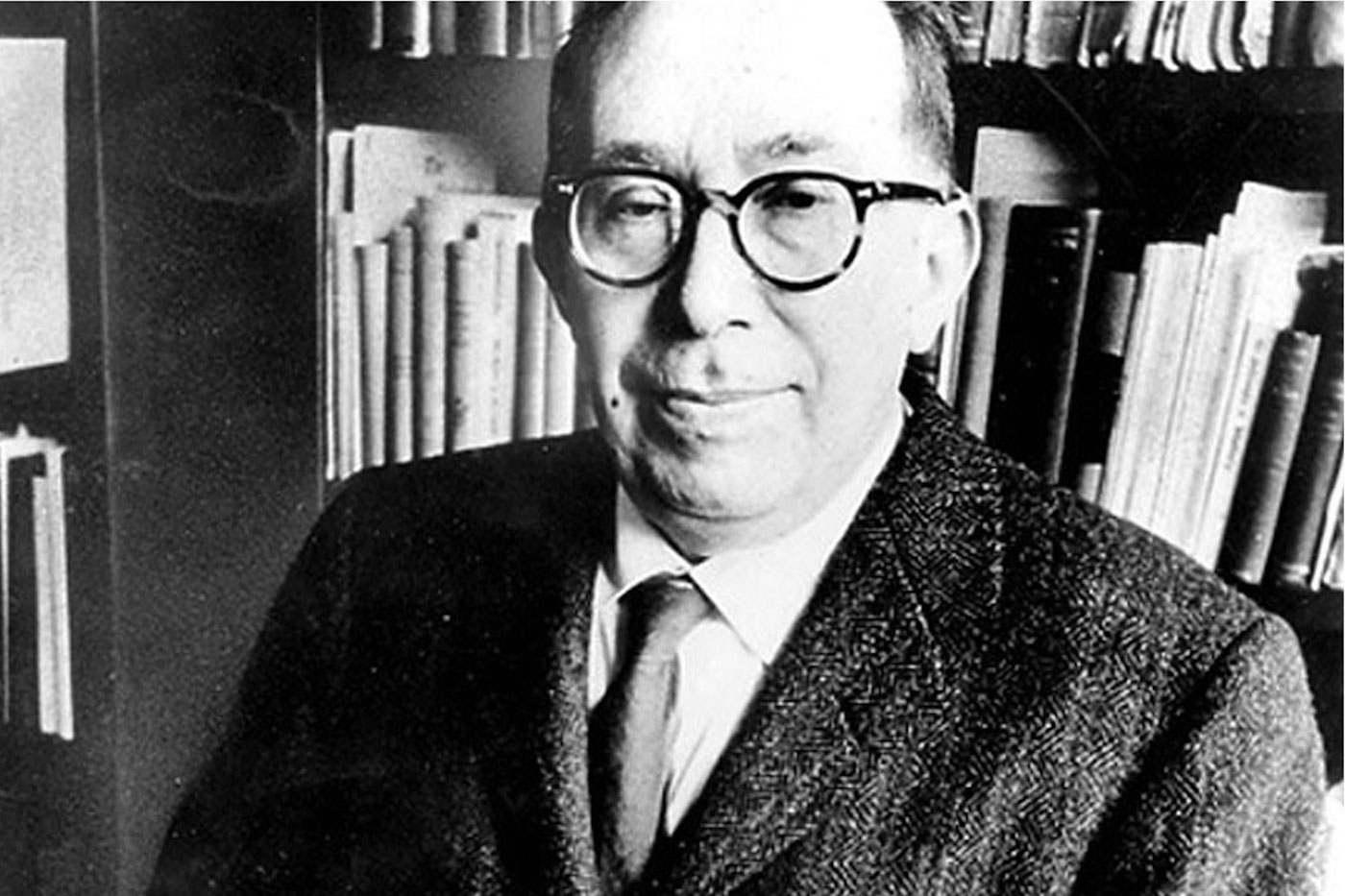

Faith, Reason, and Leo Strauss

APRIL 5, 2019BY KODY WAYNE COOPERBoth believing and non-believing students of Strauss will find Leo Strauss and His Catholic Readersrewarding.

A book titled Leo Strauss and his Catholic Readers might initially seem strange. Is there common ground between an apparently non-believing Jewish political philosopher and a handful of believing Roman Catholic political philosophers? This volume demonstrates that the faithful Catholic does share a range of common goals and interests with Strauss. To name just a few, there is a shared belief in natural standards of the just and the good, a deep interest in the relationship between faith and reason, and a faith in reason’s ability to transcend its own historical context and arrive at enduring truths.

While Strauss himself is dead, his words and influence live on in his works, his students, and his thoughtful readers. One is reminded of what Adams said to Jefferson when they famously renewed their correspondence in retirement. It is the belief of this impressive crop of scholars that Roman Catholics and Leo Strauss ought to explain themselves to one another. The result is a treasure trove of reflections on a range of themes in Strauss’s thought, accompanied by explanation of the areas of agreement, and a careful, charitable explanation of Catholics’ reasons for disagreement.

The book is a collection of essays, bringing together the work of an impressive array of scholars. It is divided into three parts. Part one revolves around themes connected to Strauss’s recovery of natural right and his qualified appreciation―but ultimate rejection―of Thomistic natural law. It includes Robert P. Kraynak’s wide-ranging essay on reason and faith in Strauss, V. Bradley Lewis’s account of Charles N.R. McCoy’s engagement with Strauss, Geoffrey Vaughan’s defense of Strauss’s worries about the rigid and idealistic features of natural law, Marc Guerra’s comparative study of Strauss and Benedict XVI, and Douglas Kries’s study of Fr. Ernest Fortin’s encounter with Leo Strauss.

Part two brings together essays exploring common concerns of Catholics and Strauss. Gladden Pappin explores how A.P. d’Entrèves, Charles McCoy, and Yves Simon thought about the relationship of philosophy to society in comparison and contrast with Strauss. John Hittinger analyzes a lecture Strauss gave at the Jesuit University of Detroit and finds useful lessons for Catholics. Carson Holloway rereads Strauss’s lecture “Progress or Return” and defends a Catholic approach to the theologico-political problem. Gary Glenn contends Catholic natural law has a flexibility akin to natural right. J. Brian Benestad’s essay wraps up this section with a Straussian critique of historicist Catholic theology.

Part three is titled “Leo Strauss on Christianity, Politics, and Philosophy.” Giulio de Ligio reflects on the relation in Strauss’s thought between politics and philosophical investigation. In one of the most interesting chapters, James R. Stoner argues that Strauss accepted classical teleological metaphysics as a true account of nature. Philippe Bénéton brings Strauss into dialogue with Pascal. Finally, Ralph C. Hancock (the only non-Catholic contributor) explores Strauss’s critique of Christianity.

There is a substantial overlap in the themes explored across the sections of the book. Sometimes a chapter can feel quite different from the others with which it is grouped, and one could make a case for ordering the chapters differently. There also are arguably some gaps in what the book covers. For example, readers might want to see more engagement with the work of Fr. James Schall, who is correctly said to be “preeminent” among the Catholic readers of Strauss.

Still, both believing and non-believing students of Strauss will find this book rewarding. Most will agree with Hittinger that “the challenge to read political philosophers in a fresh, non-derivative way” is perhaps Strauss’s greatest legacy. In its own fresh, non-derivative reading of Strauss and his interlocutors, this book contributes to repaying the debt Catholic political philosophers owe to Strauss for the revival of political philosophy.

About the Author

KODY WAYNE COOPER

Kody W. Cooper is Assistant Professor of Political Science and Public Service at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and author of Thomas Hobbes and the Natural Law (University of Notre Dame Press, 2018).

RELATED POSTS

- Leo Strauss and American ConservatismContrary to popular belief, Leo Strauss was not a conservative, let alone a neoconservative. Yet…

- Contra Leo Strauss, There’s No Conflict Between Reason and RevelationStrauss’s account of reason and revelation seems to depend for its intelligibility on an account…

- Leo Strauss and the Pursuit of Knowledge: A Reply to Paul DeHartLeo Strauss’s statements on philosophy do not deny that knowledge is possible. Rather, they emphasize…

LATEST ARTICLES

Faith, Reason, and Leo Strauss

What American Conservatives Can Learn from Canada

When Reason Does Not Suffice: Why Our Culture Still Accepts Abortion

Anti-Discrimination “Equality” Law Exemptions Do Not Lead to Fairness for All: An International Perspective

BY PAUL COLEMAN

Striving for Digital Minimalism: Why We Need a Human-Centric Approach to Technology

BY CASEY CHALK

We Were Parents

Catholic Thought and the Challenges of Our Time

Of The Diversity Delusion, Delivered

Whither Humane Economics? In Defense of Wonder and Admiration in Natural Science

Can Hatred of Christians Lead to Support of Sexual Minorities?

Humanizing the Venezuelan Collapse: Beyond Economic Indicators and Policy Briefs

Donald Trump Was Elected Because Elites Have Failed the Working Class

A City upon a Hill: Nationalism, Religion, and the Making of an American Myth

The Economics and Ethics of “Just Wages”

Thomas Aquinas on the Just Price

Outrage Mobs Might Be More Forgiving If They Believed in Hell

Elizabeth Anscombe’s Philosophy of the Human Person

BY MICHAEL WEE

Taking a Closer Look at Diversity on College Campuses

Politicizing Pediatrics: How the AAP’s Transgender Guidelines Undermine Trust in Medical Authority

BY LEONARD SAX

Venezuela’s Agony, the Catholic Church, and a Post-Maduro Future

BY SAMUEL GREGG

The Scandalous Academy: Social Science in Service of Identity Politics

BY SCOTT YENOR

Lay Review With Teeth: What (Didn’t) Happen at the Vatican’s Sexual Abuse Summit

The Meaning of Meaninglessness

Humanly Speaking: Aristotle, the First Amendment, and the Jurisprudence of Pornography

Putting Adam Smith Back Together

BY SAMUEL GREGG

Pilgrimage and the Christian Life: A Lenten Meditation

Birth Control, Blood Clots, and Untimely Death: Time to Reconsider What We Tell Our Teens?

BY LYNN KEENAN AND GERARD MIGEON

Equip Yourself to Become A True Trans Ally: Read Walt Heyer’s Trans Life Survivors

The West is a Third World Country: The Relevance of Philip Rieff

Are We All “Cat Persons” Now? How Modern Dating Destroys Intimacy

BY NATHAN SCHLUETER AND ELIZABETH SCHLUETER

Professor Hittinger’s assertion that Strauss opened the way to reading ‘political philosophers in a fresh, non-derivative way’ almost seems to be rather ironic.

While Strauss and his disciples often portray themselves as fulfilling that mandate impeccably, there are, arguably, numerous instances in which they bring to their task numerous tacit rationalist presumptions.

This is why the complex details and specific concretely realized utilizations and refinements of ‘classical’ sources, both practical and speculative, during the 1000 years or so of the variegated Christian dominance among European nations in that era are, on the whole, bracketed or prescinded from entirely by Strauss and those who insist he was the exemplar of scholarship concerning matters philosophical. It remains striking how, overall, the project of Strauss and his supporters seems to reduce what is worthy of thorough examination within the sweep of Western history to what was the Classical and the Classical-Modern.

Yes, shared concerns there are, and were, among Strauss and certain prominent Catholic figures in philosophical issues. But once one begins to consider the lack of assent to certain important principles, rationales and conclusions that some of the latter held, which were derived from their heritage, one wonders, in the depths, just how substantive the common concerns might be.

Thanks. I read that book about three months ago and gave it to a Matthew Moore to read. I’ve read a handful of Strauss’s books, and am a fan of one of his Catholic students, Ernest Fortin.

Sent from my iPhone